How’s this for a story? In 1920, a young woman dressed entirely in black walks into the foyer of a Monte Carlo hotel clutching the scores of a couple of pieces of music. She’s on a mission. Staying at the hotel is the American violinist Albert Spalding, nephew of the founder of Spalding sporting goods. The woman approaches the violinist and thrusts the music into his hand before disappearing. Spalding would later say he was “accosted”, but he didn’t mind – he went on to play those two pieces publicly hundreds of times, and that’s one of the ways we’ve come to know the music of the woman in black’s best friend, French composer Lili Boulanger.

The woman, Miki Piré, was in mourning. Lili had died of Crohn’s disease in 1918, aged just 24, and Miki had taken it upon herself to help get her music out there, however she could. They were very close – close enough to have swapped keepsakes at the outbreak of the First Wold War in case they never saw each other again – and Miki would have known that Albert Spalding had met Lili and her family in 1912. She took her chances in that Monte Carlo hotel and it worked. But she wasn’t Lili’s only champion – Lili’s sister Nadia would go on become one of the 20th century’s most-renowned music teachers, and it was Nadia who supervised the release of this extraordinary 1960 album of works by Lili, a “world premiere recording”, although it came out 42 years after Lili died. “For Nadia Boulanger,” the sleeve notes say, “this was a great moment. It had been a lifelong ambition to have her younger sister’s compositions recorded.”

It’s impossible to right the wrong of the lost place of the female composer in history, but in recent years much has been done to at least document better what was achieved (and continues to be achieved). More women composers were recorded on CD than in the much-longer vinyl era, and there’s a forever-increasing appetite to know more about their lives. I can recommend Anna Beer’s Sounds And Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women Of Classical Music, which was published last year and includes a chapter on Lili Boulanger, and an online BBC Radio 3 collection of programming, Celebrating Women Composers, also featuring the subject of this month’s column.

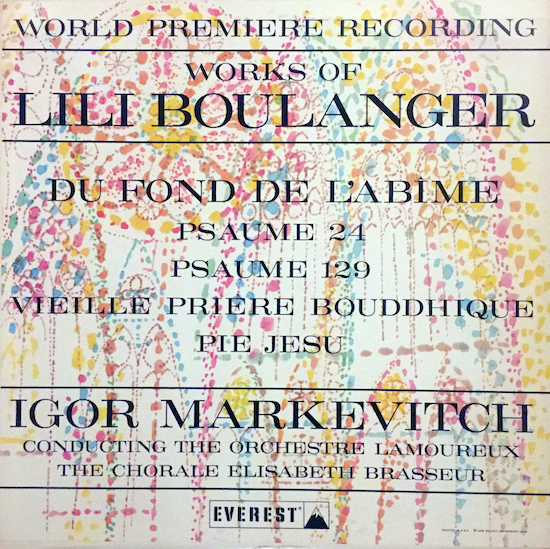

It’s probably not an exaggeration to say that Lili’s music is better-known in the internet age that it’s ever been, although she remains a fringe figure in the story of music. Her LPs – the few that exist – are not exactly easy to find and it was fortuitous that I stumbled upon this album, recorded in Paris but released on a long-gone US indie label, Everest. It was tucked away in a box of beautifully preserved, entirely North American-released records dropped off at a charity shops in St Albans. I bought the lot, tried this album first and I was floored by its towering and strange opening track – the 24-minute ‘Du Fond De L’Abîme’ (‘From the depth of the abyss’), which takes up side one. I’d never heard anything like it before and I haven’t since, and the four shorter pieces on the second side are just as intriguing.

With so many great artists dying young and/or battling illness, physical and mental, we risk becoming immune to the tragedy in their story. With Lili Boulanger, you can’t do that; you can’t forget that she wrote all of her music by the age of 24 and was sick from the age of two onwards. In music history, she’s most famous for being the first female winner of prestigious Prix de Rome (previous winners included such giants of French music as Berlioz and Debussy), after which she was described as “a slim shadow in a white dress” who had “frail grace”. The image of Lili being weak and waif-life stuck (and, in a man’s world, she may have played up to it, appearing unthreatening to gain advantage), but it doesn’t add up; she was weak through illness, but ‘Du Fond De L’Abîme’ is not fragile music, or particularly graceful – it’s thunderous and enormous, and seems “to open in the very bowels of the earth… despair, entreaty and terror”, as the British composer Christopher Palmer said.

Lili Boulanger’s family story is a complex mix of privilege and the bizarre. Both her grandfather and her father were teachers at the Paris Conservatory, and celebrated musicians in their own right. Her father Ernest also won the Prix de Rome (in 1835, aged 20) and he was a bachelor in his 60s when he married Lili’s mother Raissa, one of his students and possibly a Russian princess, although no one is absolutely sure whether that’s true. It’s speculated that they had four daughters, two of whom died very young, but one biographer questions whether Ernest was the father of any of the girls, suggesting an alternative scenario, without proof, that is too weird to seem plausible – that Lili was the daughter of an obese womaniser who would later become her sister Nadia’s much-older lover, and Nadia was the daughter of a man whose son Lili apparently got engaged to in 1914. The obese man, composer and music teacher Raoul Pugno, certainly became a significant male figure in the family’s life after Ernest died in 1900 and perhaps the only thing we can say for sure is that Lili was devoted to Ernest and devastated by his death. Nadia thought it was the pivotal moment in Lili’s life, saying: “I believe that her whole talent was rooted in her first knowledge of grief. When our father died, she was six years old, and at six she understood what death was – it is the grief of surviving someone you love.”

Some of the biggest figures in turn-of-the-century French music were friends of the Boulangers, including Maurice Ravel and Gabriel Fauré, who taught Lili. Both Nadia and Lili were swamped by music as they grew up, and they excelled at it. However, it fell to Lili to reclaim the Prix de Rome for the family after Nadia – six years Lili’s senior – tried and failed four times (although during her 1908 attempt she managed to royally piss off a judge, the misogynist composer Camille Saint-Saëns, causing a scandal that made her famous across France and beyond). Lili first entered the prize in 1912, but was forced to pull out because of poor health. When she won the year later, she was the youngest competitor by six years and was praised by Debussy (below), her biggest musical inspiration alongside Wagner. “Mademoiselle Lili Boulanger is only 19,” Debussy said. “Her experience of the different ways of writing music seems much older.”

In 1913, the Prix de Rome – established in 1663 and abolished in 1968 – had categories for architecture, painting, sculpture, engraving and music, and winners won a four-year bursary to study at the French Academy (Villa Medici) in Rome. For reasons no one is quite sure of (illness, most likely), Lili was months late to turn up – arriving in March 1914 with her mother in tow – and she was back home in Paris again by 1 July, just before the outbreak of war. According to Anna Beer’s Sounds And Sweet Airs, she “remained committed to a career as a composer, but not necessarily the Villa Medici way”. Like Nadia, she had a rebel spirit, completing works like her song cycle ‘Clairières dans le ciel’ (‘Clearings in the sky’) that went far beyond her requirements at the academy and chipping away at three musical settings of Psalms, all of which are included on this record.

Album opener ‘Du Fond De L’Abîme’ is a setting of Psalm 130 and I think it bears some relationship to Sibelius’s Symphony No. 4 that I wrote about in the first of these Junk Shop Classical columns. Both begin with a dramatic sense of impending doom, but where it’s likely that Sibelius’ symphony, written in 1911, was a response to his fear of death by cancer, it’s been posited that Lili’s work – a cantata, which is a medium-length narrative piece for voices with instrumental accompaniment – was a reaction to war. But maybe that’s too easy an interpretation, or just one way of looking at it. The score says that it’s dedicated to the memory of her father, making it a requiem too, and Beer goes one step further in her book, noting that Lili had returned to Rome in 1916 where a doctor apparently told her – accurately, if the story’s correct – that she had two years to live. “Is it too much to suggest that the composer was, consciously or unconsciously, writing her own requiem whilst in Rome for the second time?” Beer writes.

There is a piece on this album, ‘Vieille Prière Bouddhique’ (‘An old Buddhist prayer’ for peace and humanity) that’s definitely a response to war and, like the three Psalms, it’s a large-scale choral work. The only piece that’s small-scale is the closer, ‘Pie Jesu’, which Lili began when she was 16, probably as part of an uncompleted requiem mass. Sparse, haunting and quite unlike the very Wangerian other pieces on the album, it might have been the final work that Lili completed, but she needed help. Very sick, bed-ridden and living in Mézy-sur-Seine to escape the bombs that were raining down on Paris in early 1918, she had to dictate ‘Pie Jesu’ to Nadia, note by note. She finished the piece with a serene “Amen” and died on 18 March 18, a few days before Debussy.

Works Of Lili Boulanger was recorded by the Lamoureux Orchestra with the Elisabeth Brasseur Choir conducted by a hugely respected Russian, Igor Markevitch, and part of its attraction as a record is quite how of its time it sounds – as much like 1960, when it was released, as the 1910s, when the music was written. I don’t think it’s demeaning to say that you could imagine these pieces soundtracking film noir or even a Jacques Tourneur horror flick like 1957’s Night Of The Demon. The three Psalms are religious works, but they’re also highly cinematic and to this day I can’t understand why producers like RZA, Madlib or anyone else looking for an eerie loop haven’t sampled the opening bars of this exact version of Lili’s ‘Psalm 129’.

If they had, they would have done their part to keep Lili’s music alive, just as Miki Piré and Nadia did, the latter living to the ripe old age of 92 (she died in 1979). “It is easy to see her as the most influential teacher since Socrates,” American composer Ned Rorem wrote of Nadia in the New York Times in 1982, while also saying there were “tears on cue at mention of her dead sister”. She must have endlessly wondered what Lili would have achieved had she lived past the war, and in that she wasn’t alone. The respected writer on music Jacques Chailley believed that Lili’s accomplishments in music are unique, arguing that no other composer who died young – whether Mozart (35), Schubert (31) or Purcell (36) – had completed works on the scale of Lili’s three Psalms by the age of 24. We know that before she died she was frantically working on a modern, forward-thinking opera, Maleine, and if she’d finished it, it might well have made her name. “It would have boldly broken into traditionally male territory, and one of its most powerful institutions, the Paris Opéra,” Anna Beer writes in Sound And Sweet Airs. “She would have joined the great composers. If only.”